There are great movie years, like 1939, Hollywood’s “Annus Mirabilis,’’ and 1974-1976 (“The Godfather: Part II,’’ “Chinatown,’’ “Nashville,’’ “Taxi Driver,’’ the list goes on). There are awful movie years (take your pick). Then there are movie years that, looking back, seem to disappear in what was going on around them. Artistically, culturally, socially: It’s almost as if they vanish.

Consider 1966.

The upheaval that was the Sixties was well underway. China’s Great Cultural Revolution began. A Time magazine cover asked “Is God Dead?’’ Bob Dylan released “Blonde on Blonde,’’ the Beatles “Revolver,’’ the Rolling Stones “Aftermath.’’

You hardly would have known that from watching the big screen. With a few exceptions — Andy Warhol’s “Chelsea Girls,’’ say, or “The Battle of Algiers’’ — all seemed quiet on the movies front. The year when all Sixties hell broke loose was 1967. “Bonnie and Clyde’’ and “The Graduate’’ became cultural touchstones. The year’s biggest star, Sidney Poitier, was black. However gingerly, the three hits he starred in confronted the state of race relations: “To Sir, With Love,’’ “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,’’ nominated for 10 Oscars and winner of two, and best picture winner “In the Heat of the Night.’’

The best picture winner in 1966? That would be“A Man for All Seasons,’’ which also won Oscars for actor (Paul Scofield), director (Fred Zinnemann), adapted screenplay, cinematography, costume design. It was “Wolf Hall’’ inside out, with Scofield’s Sir Thomas More as hero. Tubby, unctuous Leo McKern plays Thomas Cromwell — no Mark Rylance he. The closest thing to a Sixties connection is that “Man’’ could have been the opening night feature at a Vatican II film festival. Its Catholic-intellectual hero was a saint, a man of thought and conscience. He even wore his hair long.

Four of the five biggest movies at the box office were costume dramas or epics. “Man’’ was fifth. First was John Huston’s“The Bible: In the Beginning’’ (that subtitle sure sounds like it’s prepping a sequel), with “Hawaii’’ second, and “The Sand Pebbles,’’ set in China in the 1920s, fourth.

Third? That was a drama, all right, but the costumes were tweed-jacket drab. The film adaptation of Edward Albee’s play “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’’ seemed very raw at the time. It starred Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Watch the most famous married couple in the world humiliate each other! But it’s not so much a departure from that very ’50s sub-genre, domestic drama — “Come Back, Little Sheba’’; “The Rose Tattoo’’ — as its culmination/demolition. The film’s ’50s-ness extends to its being in black and white.

“Who’s Afraid’’ was Mike Nichols’s debut as a film director. A year later, Nichols would win a director Oscar for “The Graduate.’’ Francis Ford Coppola, all of 27, made his debut as a feature film director, too, with the aptly titled “You’re a Big Boy Now.’’ William Goldman began what would become a legendary screenwriting career with “Harper.’’ Making their first screen appearances in 1966 were Bette Midler (“Hawaii’’), Harrison Ford (“Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round’’), Michael Douglas (“Cast a Giant Shadow’’), and Helen Mirren (“Press for Time’’).

Conversely, Cary Grant starred in his final movie, “Walk, Don’t Run.’’ John Ford directed his last film, “7 Women.’’ Fellow pantheon filmakers Alfred Hitchcock (“Torn Curtain’’), Howard Hawks (“El Dorado’’), and Billy Wilder (“The Fortune Cookie’’) definitely began to show signs of age.

The French New Wave was showing its age, too. A very different kind of French filmmaker, Claude Lelouch, took the foreign language Oscar with a very Old Wave film, “A Man and a Woman.’’ Soldiering on was Jean-Luc Godard — now there was Sixties cinema — with “Masculin Féminin.’’ Its famous intertitle, “This film could be called The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola,’’ is about as Sixties as you can get. As against that, Godard’s New Wave counterpart Francois Truffaut adapted Ray Bradbury’s novel “Fahrenheit 451’’ for Universal. Working on it, Truffaut wrote, was his “saddest and most difficult’’ filmmaking experience.

Another foreign director, Michelangelo Antonioni, made his English-language debut, with “Blow-Up.’’ The film’s Sixties credentials are very much in order, since it’s set in Swinging London. It’s hard to imagine three other ’66 films being set anywhere else: “Alfie,’’ starring Michael Caine, “Georgy Girl,’’ starring Lynn Redgrave, and “Morgan!,’’ starring Vanessa Redgrave. Both Redgrave sisters were nominated for best actress, losing the Oscar to Taylor, in “Who’s Afraid.’’

How non-Sixties was ’66? There was no Beatles movie. There was a Herman’s Hermits, “Hold On!’’ and not one, not two, but three Elvis movies: “Frankie and Johnny,’’“Paradise, Hawaiian Style,’’ and “Spinout.’’

There was no Bond movie in ’66 either. That didn’t mean any shortage of spy movies. Caine’s Harry Palmer (“Funeral in Berlin’’) is a poor man’s Bond. James Coburn’s Derek Flint (“Our Man Flint’’) is an even poorer man’s Bond. And Dean Martin’s Matt Helm (“The Silencers’’ and “Murderers’ Row’’) you don’t want to know about. Throw in “The Quiller Memorandum’’ and “Our Man in Marrakesh,’’ and you can see that spy movies were becoming the ’60s equivalent of westerns.

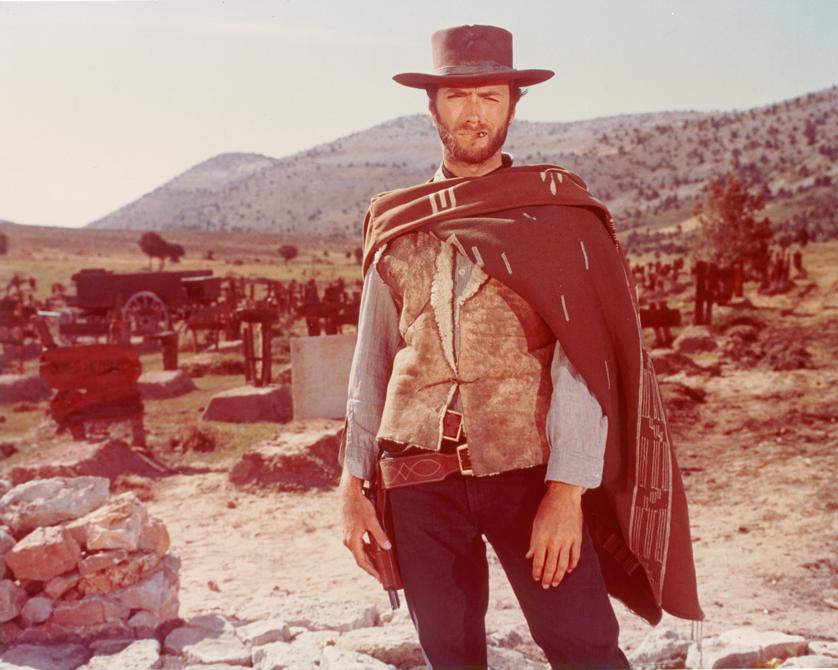

Not that ’66 lacked for westerns. There were good ones (“Duel at Diablo,’’“The Professionals’’), a Rat Pack one (“Texas Across the River’’), an extremely ill-advised one (a remake of Ford’s “Stagecoach’’), a Jack Nicholson-scripted one (“Ride in the Whirlwind’’), and a legendary one.

That would be “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,’’ the concluding film in Sergio Leone’s Man With No Name trilogy. It says a lot about the incongruity of 1966 onscreen that Ennio Morricone’s score, with one of the most memorable themes in movie history, wasn’t even nominated for an Oscar. The winner was a lion king: John Barry’s music for “Born Free.’’

As a spaghetti western, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’’ was sort-of foreign. Foreign film had had an enormous impact on US filmmakers and arthouse audiences earlier in the decade. They loomed less large in 1966. Neither Federico Fellini nor Akira Kurosawa released a film, for example. Still, both Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson did, and what films they were: “Persona’’ and “Au Hasard Balthazar.’’

Buster Keaton and Walt Disney died. Even as he battled lung cancer, Disney managed to produce “The Fighting Prince of Donegal,’’“The Ugly Dachshund,’’“Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N.’’ (the year’s seventh-largest grosser), and “Follow Me, Boys!’’ Sixties, what Sixties? At least Mary Poppins got high, albeit with an umbrella.

By Mark Feeney | Globe Staff

Mark Feeney can be reached at mfeeney@globe.com.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE