WASHINGTON — He portrayed the vapid man-on-the-street reporter Wally Ballou, ‘‘winner of over seven international diction awards.’’ He was the pitchman for Einbinder Flypaper, ‘‘the brand you’ve gradually grown to trust over the course of three generations.’’

And he was Harlow . . . P. . . . Whitcomb, who spoke with exasperatingly long pauses as ‘‘president . . . and . . . recording . . . secretary . . . of the . . . Slow . . . Talkers . . . of . . . America.’’

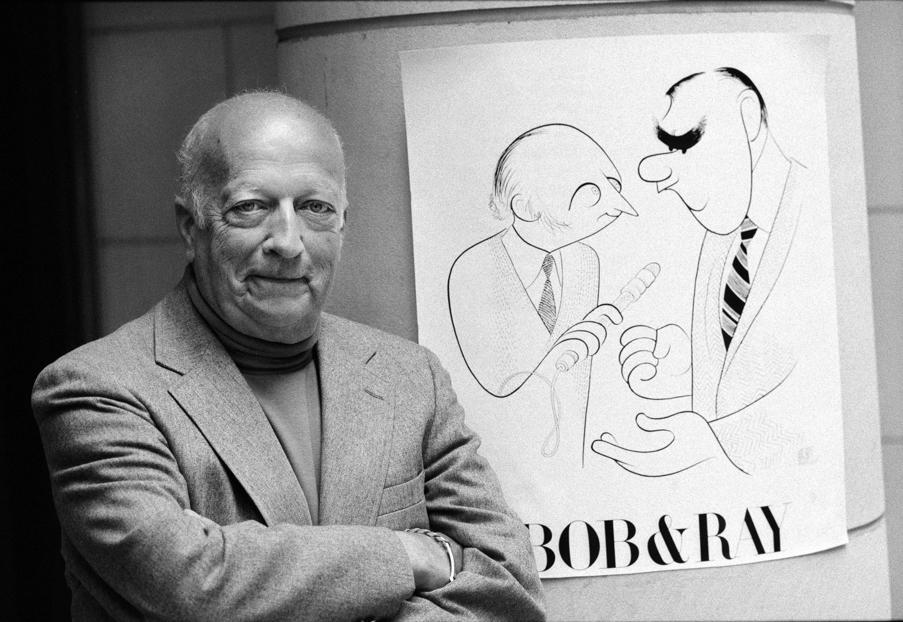

In a career that was as ridiculous as it was sublime, Bob Elliott, who died Tuesday at 92 in Cundys Harbor, Maine, was half of the comedy team Bob and Ray. The Boston native and the late Ray Goulding were among the drollest and most inventive pop-culture satirists of their generation.

Mr. Elliott also was the patriarch of a comedy family that included his actor-writer son, Chris Elliott, and a granddaughter, actress-comedian Abby Elliott, both former cast members of ‘‘Saturday Night Live.’’ Chris Elliott confirmed the death, citing throat cancer as the cause.

Bob Elliott’s show-business legacy rested on his partnership with Goulding, who died in 1990. On the radio, the duo’s primary medium, they broadcast ‘‘from approximately coast to coast,’’ as they liked to say, on outlets including CBS and National Public Radio. They were a seminal influence on entertainers including Woody Allen, David Letterman, Jonathan Winters, and ‘‘Saturday Night Live’’ creator Lorne Michaels.

A hallmark of Bob and Ray comedy was bone-dry delivery of the absurd.

With masterly timing — Mr. Elliott with a nasal deadpan, Goulding with booming authority — Bob and Ray mocked the banalities of newscasts, politics, sports, and advertising.

“The target of Bob’s and Ray’s satire is everyday human foolishness. Their humor is pointed, but never mean-spirited,’’ the Globe’s Diane White wrote in 1983. “Their two-man repertory company of fools, bores, curmudgeons, stumblers, bumblers, braggarts, eccentrics, dupes, lunatics, deluded souls, and shameless self-promoters has kept their fans enthralled since 1946, the year they began working together on WHDH radio in Boston.’’

One of their favorite skits involved Ballou interviewing a paperclip tycoon who tackles ‘‘waste and inefficiency’’ by running a sweatshop of indentured servants. Employees, earning 14 cents a week, are bound by a ‘‘99-year sweetheart contract’’ and imprisoned if they quit.

‘‘How can anybody possibly live on 14 cents a week?’’ Ballou asks. Goulding, as the industrialist, replies defensively, ‘‘We don’t pry into the personal lives of our employees, Wally.’’

Their playfully warped sensibilities often involved sly commentaries of the conventions of radio and TV, and the people who take those mediums seriously.

New York Times critic Clive Barnes wrote: ‘‘They work masterfully close to the very things they are gently mocking, and this gives their sensible nonsense its special flavor. For one thing it shows just how much arrant nonsense we actually accept in television.’’

Recurring characters included sports reporter Biff Burns, who once interviewed the world-champion ‘‘low jumper,’’ and the women’s show host Mary McGoon, who meandered from everyday recipes (frozen ginger ale salad, pabulum popsicles) to homespun medical advice (her cold remedy: goose fat in an Argyle sock, hung around the neck).

Bob and Ray voiced a panoply of overwrought characters from faux soap operas such as ‘‘General Pharmacy,’’ ‘‘Garish Summit,’’ and ‘‘Mary Backstayge, Noble Wife’’ (a parody of a long-running radio saga, ‘‘Backstage Wife,’’ about a woman named Mary Noble).

Daring for the time, they used sequences in ‘‘Mary Backstayge’’ to satirize Senator Joseph R. McCarthy’s anti-Communist crusade; the demagogic Wisconsin Republican was reimagined as Zoning Commissioner Carstairs, a ruthless opponent to building permits that would undermine the way of life in bucolic Skunk Haven, Long Island.

Decades later, Bob Elliott told The New York Times he and Goulding often went to a bar near the radio studio to watch the televised McCarthy hearings. ‘‘Then we’d use the material in the next day’s show,’’ he said. ‘‘I consider that, from a creative point of view, one of the top things we did.’’

They always closed their shows with the same signoff: ‘‘This is Ray Goulding, reminding you to write if you get work.’’ ‘‘And Bob Elliott, reminding you to hang by your thumbs.’’

Admirers extended far beyond show business figures such as Allen and Letterman. One of their most devoted fans was novelist Kurt Vonnegut Jr., who wrote in a foreword to the 1975 collection ‘‘Write If You Get Work: The Best of Bob & Ray’’: ‘‘They feature Americans who are almost always fourth-rate or below, engaged in enterprises which, if not contemptible, are at least insane.

‘‘And while other comedians show us persons tormented by bad luck and enemies and so on, Bob and Ray’s characters threaten to wreck themselves and their surroundings with their own stupidity. . . . Man is not evil, they seem to say. He is simply too hilariously stupid to survive.’’

Robert Brackett Elliott was born in Boston on March 26, 1923, and he grew up in nearby Winchester. His father, who sold insurance, introduced him to the wry humor of author Robert Benchley. His mother refinished antiques.

While attending Winchester High School, Bob, an only child, developed his radio skills over the school’s public address system.

After his Army service in World War II — he was in the supply corps in Europe — the comic partnership coalesced on Boston’s radio station WHDH.

Mr. Elliott was a disc jockey and Goulding a news announcer, and they began improvising during the dead air between segments. “It wasn’t always funny,’’ he recalled, “but it was something.’’

Within a few months, WHDH gave them their own show. New Englanders liked their patter so much that the station soon gave them another, “Breakfast With Bob and Ray.’’

After five years in Boston, they went to New York, auditioned for NBC, and were given a 13-week contract for both radio and TV.

‘‘The Bob and Ray Show’’ often featured ad-libbed moments, but also relied on writers to contribute sketches. The TV cast included Cloris Leachman and Audrey Meadows.

‘‘The Bob and Ray Show’’ was heard on CBS and Mutual Broadcasting System; its last incarnation aired on National Public Radio, 1982 to 1987.

In a sprawling career, they drew enthusiastic reviews in the early 1970s for their Broadway show ‘‘Bob and Ray: The Two and Only’’ and became favorite late-night guests of Johnny Carson and Letterman.

They introduced themselves to a younger audience with their 1979 appearance on a ‘‘Saturday Night Live’’ special. To Rod Stewart’s ‘‘Do Ya Think I’m Sexy?,’’ featuring Jane Curtin, Laraine Newman, and Gilda Radner as disco backup singers, Bob and Ray are seated in business attire and declaim the chorus, ‘‘If you want my body, and you think I’m sexy, come on, sugar, let me know.’’

After Goulding’s death, Mr. Elliott played the father — he called it ‘‘typecasting’’ — to Chris Elliott on the 1990s Fox TV sitcom ‘‘Get a Life.’’

His first marriage, to Jane Underwood, ended in divorce. His second wife, Lee Knight, died in 2012. In addition to his son, Mr. Elliott leaves a daughter, Amy Andersen, and son, Bob, from his second marriage; two stepdaughters he adopted, Colony Elliott Santangelo and Shannon; 11 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

Bob and Ray often were asked why they were billed in that order. Mr. Elliott once explained that their first show, in Boston, was called ‘‘Matinee with Bob and Ray,’’ because of the preference in those days for catchy rhyming titles.

He added, ‘‘It would have sounded kind of dumb to say ‘Matinob with Ray and Bob.’’’

Material from The New York Times was used in this obituary.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE