In Michael Crawford’s paintings, and in the cartoons he created for The New Yorker magazine, a spray of light or a cloak of gray shadows did more than just illuminate and define his ostensible subjects.

In one cartoon, a man wearing suspenders and a bow tie leads a clipboard-carrying visitor through an office that looks almost overcast inside. “And the dim fluorescent lighting is meant to emphasize the general absence of hope,’’ the man in the bow tie says, gesturing at the faceless workers in pods separated by half-walls.

“He loved light,’’ said Mr. Crawford’s daughter, Farley Crawford Bliss of Los Angeles. “I felt that’s where his painting got started, because he wanted to explore light and shadow.’’

While living in Greater Boston for nearly two decades in the 1970s and ’80s, Mr. Crawford began submitting cartoons to The New Yorker, working for much of that time in an attic studio in Watertown. Encouraged by a circle of friends that included many artists, he kept at it until the magazine accepted his work in the early 1980s. Even after he moved away in 1990, Boston trailed along as a subject of abstracts he painted of Fenway Park’s Green Monster.

Mr. Crawford, who told an interviewer that his path to becoming a cartoonist included everything from playing baseball to “writing English papers for cash for people in college’’ and “an ill-advised ‘teaching’ stint at a derelict Vermont ‘academy’ for Led Zeppelin zealots,’’ died of cancer July 12 in his Kingston, N.Y., home. He was 70.

Baseball was a frequent subject in his conversations and in his cartoons, where the interplay of dark and light can be seen in the drawings and in the words his subjects speak. In one cartoon, a pair of Red Sox players converse in a Yankee Stadium dugout, their caps casting shadows on their faces. “Hookers? Tomorrow? I thought we were doing the Guggenheim,’’ one player says.

When writing prose, Mr. Crawford filled his sentences with images that seemed only a step away from leaping onto a sketchpad or canvas. In a childhood recollection that he included in his introduction to “The New Yorker Book of Baseball Cartoons,’’ Mr. Crawford wrote about riding with his sister in the back seat of his family’s Ford while their parents listened to the Yankees on the radio.

“My dad drove with the window down, his white Brooks Brothers sleeve rolled up, elbow stuck out in to the sunshine, freckling,’’ Mr. Crawford wrote. “Both his and my mom’s vent windows were raked at broad angles, spinning cool air like fans into the back seat.’’

Before turning to art and cartooning full time, Mr. Crawford had been an English teacher, and he “was very literary,’’ said his wife, Carolita Johnson, who also is a New Yorker cartoonist, and who met Mr. Crawford in 2002. “I would say literature and art went hand in hand for him.’’

“Michael Crawford was a cartoonist and a painter, a wry and sensitive artist who woke each day with his head full of dreams,’’ David Remnick, the New Yorker’s editor, wrote in a “Postscript’’ tribute after Mr. Crawford died. “Straight from bed he reached for his pencils and pad, the better to get those images and word clusters down on paper.’’

That’s not to say Mr. Crawford’s ideas arrived fully formed. “He had hundreds of drawings without captions and he would work on captions for them,’’ his wife said. “He would constantly ask me, ‘What do you think the caption for this one should be?’ ’’

The couple followed a tradition when their work was accepted. “Whoever sold a cartoon would have to take the other out for a steak,’’ said Johnson, who married Mr. Crawford this year. “And sometimes we’d both sell one, and would go Dutch.’’

Born in Oswego, N.Y., Michael Thomas Crawford was the son of Edward Crawford, who was elected to the New York State Assembly and served as a state Supreme Court justice, and the former Margaret Conlin. Mr. Crawford’s mother became a political activist, protesting nuclear proliferation and advocating on behalf of homeless children.

After graduating from the University of Toronto with a bachelor’s degree in English, Mr. Crawford spent a year at the university’s law school before engaging in a series of jobs that he mentioned in an interview for Michael Maslin’s “Ink Spill’’ blog – among them working for a Washington pollster.

Mr. Crawford’s first marriage ended in divorce. He and his second wife raised their two children while living in Western Massachusetts, where he took classes at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and in Greater Boston – first on the Somerville-Cambridge border, then in Cambridge, and finally in a Queen Anne Victorian they bought in Watertown.

After a brief stint teaching at Beaver Country Day School, Mr. Crawford began pursuing art more seriously. When he sold his cartoons at an art fair in Hyannis, he met a publisher who offered him work illustrating academic books. He also sold illustrations to Harvard University publications and in other venues.

“He got to know a fair number of artists in the Boston area,’’ said his former wife, Meg Crawford of Rhinebeck, N.Y. “A good half of our friends were artists. That was huge for Michael. He began to see himself that way, not as an English teacher, as he had been before.’’

When the family finally left the area in 1990, it was because “light was really important to him, so the gray skies of Boston got to him after a while,’’ she said.

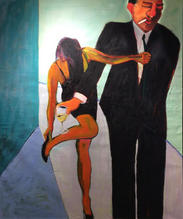

Though Mr. Crawford sold hundreds of cartoons to The New Yorker, beginning in 1981, he also painted a wide variety of subjects, including mobsters, a particular fascination. And he noted in the “Ink Spill’’ interview that on one occasion Roger Angell, a New Yorker magazine editor and baseball writer, “bought a version of my Bill Buckner’s 1986 World Series error painting at one of The New Yorker Gallery exhibits’’ in the 1990s.

A service will be announced for Mr. Crawford, who in addition to his wife, daughter, and former wife leaves his son, Miles of Los Angeles, and his sister, Kate Briscoe of Ottawa.

At dinner parties his family attended, Mr. Crawford “always loved sitting with the kids at the kids’ table,’’ his daughter recalled. “He loved to draw, and wanted to create fun wherever he went. I felt like he was a big kid always.’’

Yet Mr. Crawford also “had this incredible way of tying different concepts together in the same thought, in the same expression — in his paintings, in his cartoons, and also in life,’’ his son said.

On his phone, “the way he would text was like beat poetry. There was a bit of deciphering code because he had amassed all these cultural references that he kind of assumed everybody knew,’’ his son said, adding that on one occasion a text Mr. Crawford sent while watching a Red Sox game included a reference that linked a painter to a Red Sox player “because of the way the light hit the Green Monster behind him.’’

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE