One of the more surprising features of the crazy presidential season has been the rise of a youth movement led by a senior citizen, 74-year-old Bernie Sanders. Those under 30 show a remarkable affection for Sanders, who earlier this spring was beating Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton combined in this demographic.

Why are the youngest voters attracted to the oldest candidate? Some of the reasons are easy to see — Sanders talks a lot about free tuition and student debt relief. Others are more atmospheric — an outlaw status and all that talk of revolution.

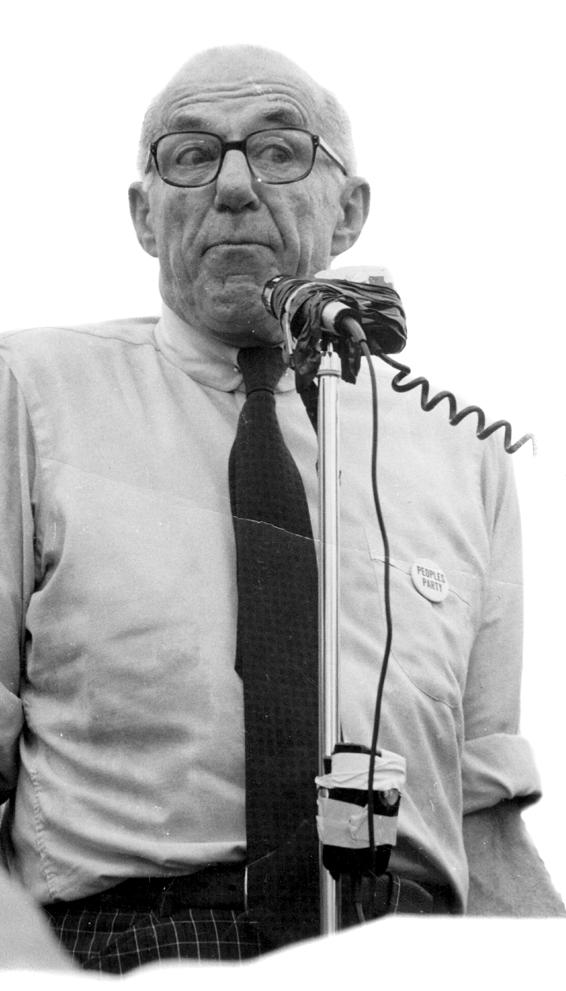

In some ways, this year resembles 1972, when a small number of young people swarmed around another elderly pied piper, the pediatrician and antiwar activist Dr. Benjamin Spock. One who fell under his spell was a newly minted Vermonter named Bernie Sanders.

Spock, 69 years old at the time, was well-known for having written “The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care,’’ which sold in phenomenal numbers during the baby boom. Indeed, Spock’s chief supporters in 1972 were the same babies whose health he had been advising mothers about for decades.

His career as a radical was surprising for a man who seemed destined by pedigree and upbringing for a comfortable place inside the establishment. Upbringing was the key to everything in those days, and Spock’s mother was an old-school matriarch, who instilled both love and terror in her six children. (Spock remembered that she would limit him to two baked beans because she feared they were unhealthy.) Spock, dutifully following family tradition, went to Andover, then Yale, where he found success as a rower — he won a gold medal at the 1924 Paris Olympics.

But something gnawed at him — a sense that upbringing could be done better. During his medical training, Spock absorbed a great deal of educational and psychological theory — the teachings of John Dewey, the influence of a movement in the 1930s that preferred teaching outdoors, and the enduring relevance of Freud to a culture that was still seeking ways to talk about sexuality.

Spock was also learning from experience, as a young parent in his own right and as a practicing doctor.

He poured all this experience into his book, which offered gentle encouragement rather than stern admonition to a postwar generation that was settling down. “Trust yourself. You know more than you think you do,’’ he wrote in 1946. Encouraged and empowered, young women went confidently into motherhood, and a new generation grew up in an environment that was more comfortable, more loving, and more free than what had come before.

Success brought unexpected celebrity to Spock. He wrote columns for magazines and found that the new medium of television favored a 6-foot, 4-inch doctor with a chiseled jaw. He sat for interviews and spoke well, and his book got a huge plug when “I Love Lucy’’ made a reference to it during Lucy’s much-watched on-air pregnancy.

Politics gnawed at him as well. In 1956, he supported Adlai Stevenson for president and, four years later, backed JFK in a big way. It helped that the candidate’s wife was expecting. But the campaign also shrewdly understood that Spock had a massive influence among female voters. Journalist Theodore White wrote, “Millions of American mothers and grandmothers in the United States would as soon question Dr. Spock as they would Holy Writ.’’ Spock’s televised endorsement of JFK made a difference in an election that was won by only 50,000 votes, and Spock enjoyed an even higher level of celebrity afterward with visits to White House dinners (Spock arrived in a VW Beetle).

Even as the Cuban Missile Crisis took the world to the brink of nuclear war, Spock was already beginning to sound alarms about radioactive fallout, a public health concern relevant to his expertise. He was invited on to the board of SANE, a nuclear arms control group. It was an exciting place to be in 1963, as President Kennedy was leading the way toward a test ban treaty. SANE took out a full page ad in The New York Times, which featured Spock with a small child and a four-word headline, “Dr. Spock is worried.’’ The effect was sensational.

When Lyndon Johnson became president, he went out of his way to cultivate Spock, calling him at his hospital and assuring him that he would never send troops to Vietnam. When LBJ did just that in 1965, Spock felt personally betrayed and veered even further to the left, speaking out publicly against the war. Time sardonically called the baby doctor “The Great Pacifier.’’ He found new allies, including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who had also soured on LBJ. Spock was asked if he would ever run for office, and he replied, semi-seriously, that he would with King at the top of the ticket.

After the upheavals of 1968, many young Americans were rising up in ever larger numbers, looking for answers from an older generation that seemed to have run out of ideas. Spock was indicted for disrupting the draft and endured a highly public trial. He toured college campuses constantly, met thousands of students, and was generally the only person over 30 that most of them trusted.

By the end of the 1960s, many Americans felt as much contempt for the Democratic Party as they did for the Republicans. Third parties were attractive, and one, the People’s Party, nominated Spock to run for the White House in 1972.

The People’s Party was never much of an organization. It could get on the ballot only in 10 states and ended up winning a mere 79,000 votes. It was disingenuous to claim, as Spock did, that the two major parties were identical — George McGovern ran far to the left of Richard Nixon in 1972. But paranoia was a regrettable feature of the age.

Certainly, the right had become paranoid about Spock. By 1972, he had become a favorite target for their rage. Preacher Norman Vincent Peale specifically blamed Spock for corrupting the morals of an entire generation by encouraging their “instant gratification,’’ a remark amplified by Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, who lost no opportunity to bait the young.

Spock gave it everything an old man could. He traveled and spoke just about anywhere he was invited. He was amazed when a detail of 24 Secret Service agents was assigned to protect him and his tiny campaign. Spock paid for many of the campaign expenses himself and stayed in one student apartment after another.

One of those students, evidently, was Bernie Sanders. It’s difficult to authenticate, but a website about Sanders created by Vermont experts who have known him a long time claims that Sanders showed Spock around Vermont on Sept. 13, 1972.

Vermont was a natural place for Spock to campaign — one of his magical 10 states — and Sanders was exactly the kind of recently arrived Vermonter who would show up and take Spock around. Though too old to be a Spock baby (Sanders was born in 1941), he fit the demographic perfectly in other ways. In 1968, he had moved to Vermont full time, after growing up in Brooklyn and going to school in Chicago. That was the year that so many young Americans resolved to try to build new lives, as far away as possible from the old power structure.

Vermont’s small population (444,732 in 1970) and cheap real estate made it affordable. Its old-fashioned values also appealed to a young generation beginning to adopt farmer chic, as Jimi Hendrix gave way to Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young. Some idealists even began to think of Vermont as a state small enough to take over.

A manifesto of sorts was written by two young graduates of Yale Law School, James F. Blumstein and James Phelan, titled “Jamestown Seventy.’’ They wrote, “What we advocate is the migration of large numbers of people to a single state for the express purpose of effecting the peaceful political take-over of that state through the elective process.’’ They sought a rural place, where the alienated could go and live by the light of their new consciences, untrammeled by authority, and honoring the spirit of the early pioneers.

Of course, Vermont could never save the rest of America, or even itself, from the spread of capitalism and gas-guzzling SUVs and fast food. But in other ways — the success of Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream, the popularity of Phish, the marriage equality movement — Vermont punched well above its weight. Bernie Sanders was the messiah of this movement.

Sanders first became a political candidate on Oct. 23, 1971, in the library of Goddard College, a small liberal arts campus in Plainfield, Vt., which would later serve as the breeding ground for Phish. Another tiny antiwar party, the Liberty Union Party, wanted someone to run for Senate, and Sanders, having just turned 30, may have been the only person in the room who met the age requirement.

The Liberty Union Party was long on ideals and short on governing experience. Sanders somehow managed to run for both senator and governor in 1972, failing by wide margins. He also found time to escort Spock around the state, although Spock was technically from another party. But the differences between the two parties were small enough, and their sheer numbers so low, that one can forgive their momentary solidarity. Many of Spock’s campaign positions would be echoed by Sanders later on, including free universal education and the closing of corporate tax loopholes. Others went further: a cap on income at $50,000 and a guarantee of $6,500 for every family of four. Spock proudly remembered, “It was feminist, democratic, and socialist.’’

Sanders remained in Vermont, where he briefly pursued a career as a maker of filmstrips for children on the history of Vermont, including the presidency of Calvin Coolidge. He apparently did voice over for these films; although it’s difficult to imagine him as a plausible Coolidge. Then, in 1980, he won the mayorship of Burlington by 10 votes, and he was off to the races.

Spock remained active in liberal causes, and returned to northern New England to campaign against the nuclear power plant in Seabrook, N.H., in the late ’70s and early ’80s. He remarried and settled into a solar-powered house in Arkansas, another small mountainous state that, as it turned out, was breeding national politicians of its own in the 1970s. When Spock died in 1998, President Bill Clinton praised him as a “tireless advocate.’’ Perhaps, even today, Spock’s voice has not been entirely stilled in another hectic race, once again dominated by the baby boom.

Ted Widmer is the Saunders Fellow for Public Engagement at Brown University and a senior fellow of the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. He is also a trustee of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE