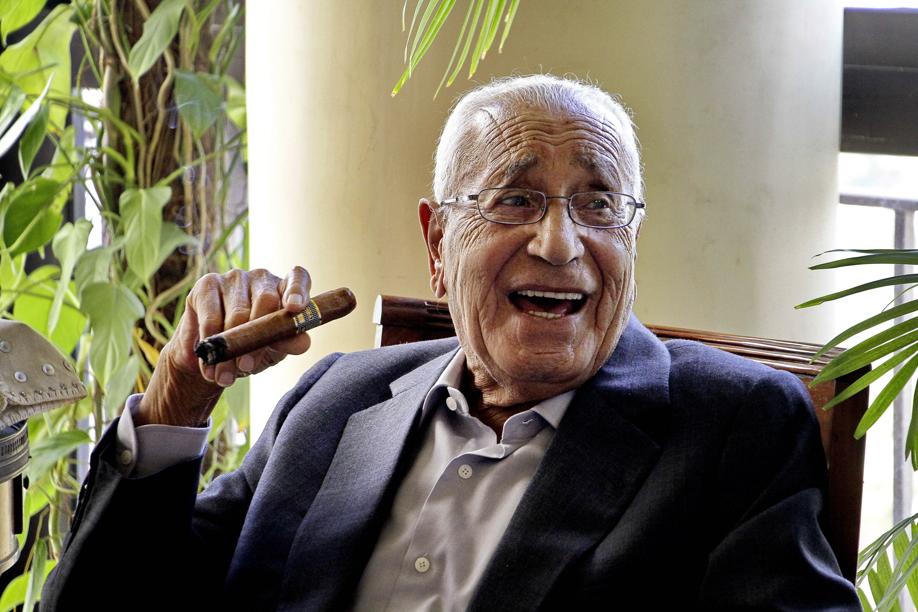

CAIRO — Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, an Egyptian journalist and historian who was an alter ego to President Gamal Abdel Nasser and for a time became an informal adviser to President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi, died here on Wednesday. He was 92.

His death was reported on Egyptian state television. He recently had kidney failure and received dialysis.

Mr. Heikal’s career was defined by his close partnership with Nasser, whom he helped write landmark speeches and a political manifesto, “The Philosophy of the Revolution.’’

Under Nasser’s patronage, Mr. Heikal became editor in chief of Egypt’s flagship state newspaper, Al Ahram, and transformed it into the Arab world’s most influential publication — not least because of Mr. Heikal’s own weekly column, “Frankly Speaking.’’

He carried private messages to and from Western diplomats as Nasser’s informal emissary. And he remained the public voice of Nasserite secular Arab nationalism long after Nasser’s death in 1970.

Even before he met Nasser, though, Mr. Heikal was among the best-known journalists in the Arab world, having begun his career during World War II as a 19-year-old reporter covering the Battle of El Alamein. Mr. Heikal went on to a six-decade career as the dean of Arab political commentators.

He wrote 40 books — often as a firsthand witness to history — on the Iranian revolution, the Israeli-Palestinian peace talks, and other matters. And, partly protected by his singular place in Egyptian history and letters, he became a thorn in the side of subsequent Egyptian presidents who sought to repudiate Nasser’s legacy.

Mr. Heikal initially served as something close to a mentor to Nasser’s successor, Anwar Sadat. But Mr. Heikal broke with the new leader over his peace with Israel and his turn toward the West.

In 1981, Sadat jailed Mr. Heikal to silence him. Sadat was assassinated a month later, and his successor, President Hosni Mubarak, promptly freed Mr. Heikal.

Mr. Heikal later insinuated that Sadat might have played a role in Nasser’s death, suggesting a possible poisoning, although at other times Mr. Heikal disavowed that theory. He also wrote an account of Sadat’s assassination, “Autumn of Fury,’’ that portrayed the killers’ plot as part of a broad national reaction to Sadat’s policies. Reviewing the book for The Times, Edward Mortimer said it “stops short of explicit admiration for their deed — but only just.’’

Mr. Heikal was also candid in his criticism of the president who had freed him. He publicly argued as early as 2002 that Mubarak, then 74, should not seek a fifth six-year term in 2005 or groom his son Gamal to succeed him. Mubarak persevered against that advice, and an uprising against his long rule removed him from power in 2011.

Mr. Heikal always described himself as a journalist, first and foremost. But his unique role as a participant in, and a chronicler of, Egyptian history drew politicians of all stripes — liberals, nationalists, even Islamists — to seek his counsel.

Born in Cairo to a wheat merchant who lived in the Nile Delta province of Qalyubia, Mohamed Hassanein Heikal — known in Egypt by his three-part name — turned away from the family business to seek a broader education at American University in Cairo.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

PREVIOUS ARTICLE