In his annual address to teachers and staff on opening day as Brookline’s superintendent, Robert I. Sperber would often describe the school system as a lighthouse, illuminating a path toward excellence.

“Bob made us feel part of something bigger than ourselves, that our work went beyond the classroom,’’ recalled Jeffrey Young, who formerly chaired Brookline High School’s English department.

As superintendent in Brookline from 1964 to 1982, Dr. Sperber was instrumental in the founding of the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity, or METCO. He also implemented innovative curriculum and support programs, including the Brookline Early Education Project; Facing History and Ourselves, a Holocaust education program; and the town’s Extended Day Advisory Council and Education Foundation.

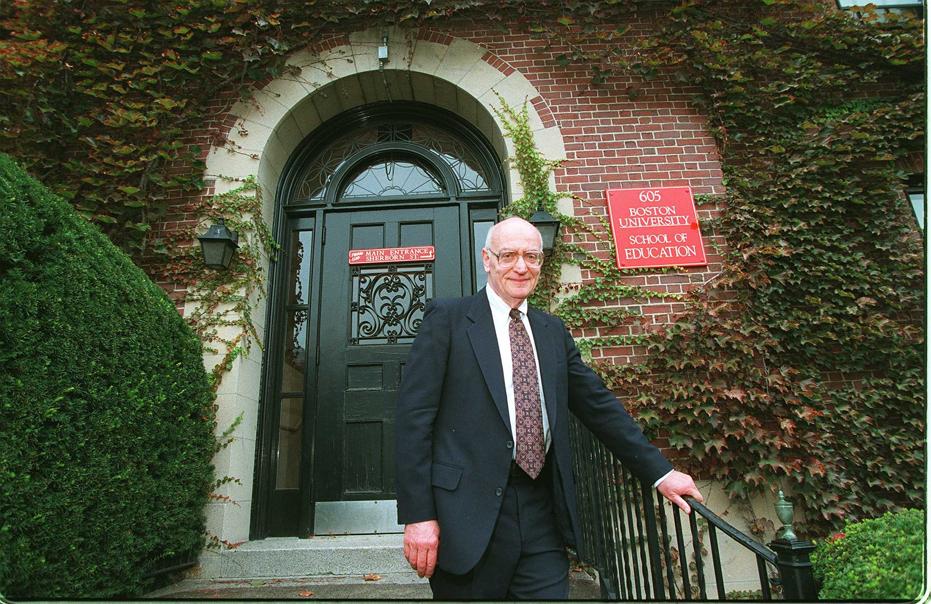

A special adviser to Boston University’s then-president John Silber after leaving his superintendent post, Dr. Sperber died of cancer Dec. 21 in his Brookline home. He was 87.

“I saw how his words, his ideas, and his heart could make a difference for students, and I am forever grateful he was my mentor,’’ said Young, a former superintendent of schools in Lynnfield, Lexington, Newton, and Cambridge.

In 1998, the Brookline Education Center was renamed the Robert I. Sperber Curriculum Center, and an annual award for educational leadership in Brookline is presented in his name.

Last April, before a gathering of more than 140 friends and former colleagues, Dr. Sperber was honored at the Brookline Teen Center, where he was a board member.

“He was an inspiration to me and many others,’’ said community activist Anne Turner, who chaired the event. “It was a special and poignant thank you, and it meant a lot to us and to him.’’

The celebration included an oral history video in which Dr. Sperber talked about his core beliefs: a commitment to equality for all students, the importance of creating innovative ideas that last, and using education as an instrument of social justice.

Barbara Senecal, who had chaired the Brookline School Committee during Dr. Sperber’s tenure, recalled that “people were standing in line to just have a moment with him’’ at the celebration, and that “he was the most ethical and moral straight-talking person I ever knew.’’

In the oral history, Dr. Sperber said that when he came to Brookline, its eight K-8 schools were unequal. He called them the “haves and the have-nots,’’ and he improved the four “have-nots’’ through better staffing and curriculum, and up-to-date textbooks.

He also upgraded the occupational education program at the high school, providing opportunities for that segment of the school population after graduation.

After Proposition 2½ — which he opposed — was implemented, Dr. Sperber decided in 1982 to resign as superintendent. The state law mandated that local property taxes could not rise by more than 2.5 percent of total assessed value annually. “It’s just been very painful for me to recommend a cutback of programs I’ve had a role in creating,’’ he told the Globe at the time.

He spent the next 20 years at BU as a specialist in urban education for the Silber administration, and as a professor of urban education. “There are vast resources in the university that could be mobilized as kind of a pool — both human and physical,’’ he said in the same interview. “We have a responsibility to offer this.’’

Dr. Sperber codirected the Boston Leadership Academy that helped train Boston school personnel, and he supervised the Boston High School Scholars Program that provided four-year scholarships at BU.

He also was on the management team for the BU/Chelsea Project when the university took over running that school system, and played a major role in the building of seven schools in that community by brokering a deal with the state.

“He came to BU with a history of innovation and creativity,’’ said Ruth Shane, former director of the BU/Boston Public Schools Collaborative. “Dr. Sperber’s commitment to equal opportunity and equal access propelled me into areas that were a hallmark of my work at the university — and he always had my back.’’

From 1982 to 1998, Dr. Sperber was executive director of the Boston Higher Education Partnership, a group of colleges and universities that worked to improve the quality of education in Boston’s schools.

“We kind of grew up together politically and publicly, and over the years Bob was the right guy in the right place at the right time and he exercised real leadership,’’ recalled Michael S. Dukakis, who lives in Brookline and was governor during most of the time Dr. Sperber led the Boston Higher Education Partnership.

Born in New York City, Robert Irwin Sperber was the only child of Jacob Sperber, a dental technician, and the former Alice Schwartz.

He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in history from the former Western Reserve University in 1951. He received a master’s in childhood education and an education doctorate in general and elementary administration from Teachers College at Columbia University in New York.

Dr. Sperber, who served in the Army from 1952 to 1954, taught third, fifth, and eighth grade in Levittown, N.Y., and was administrative assistant for the superintendent of schools in Plainview, N.Y., and Westfield, N.J.

He was hired as assistant superintendent for personnel in Pittsburgh, where he led the desegregation of the system’s teaching staff, and subsequently was chosen from among 50 candidates as Brookline’s superintendent.

In 1958, Dr. Sperber married Edith Winter, an elementary school teacher. Mrs. Sperber, who died in 2012, was director of libraries for the Lincoln Public Schools and at Hanscom Air Force Base. She also had been a Brookline Public Library trustee and an alumni trustee at Wheelock College.

A founder of the preschool program at Temple Israel of Boston, she, like her husband, was a Brookline Town Meeting member — and a gracious host. At their popular dinner parties, Senecal recalled, “Edith did the cooking and Bob washed the dishes.’’

Dr. Sperber, who donated his papers to the American Jewish Historical Society in Boston, remained active after retiring from BU. He served on the Board of Overseers at the Brookline Education Foundation and was a sought-after superintendent’s search committee member by area school systems.

“Bob was a visionary who didn’t just talk the talk,’’ said Terry Kwan, a former Brookline K-8 science supervisor. “He made it clear what his agenda was, supported you, and never lost a beat — right to the end.’’

A service has been held for Dr. Sperber, who leaves his sons, Matthew of Dunedin, Fla., and Laurence of Scarsdale, N.Y.; his daughter, Beth Sperber Richie of Silver Spring, Md., and seven grandchildren.

Burial was in Walnut Hills Cemetery in Brookline.

His son Matt, who recalled being chided by his classmates when Dr. Sperber didn’t call off school on snowy days, said in a eulogy that his parents “gave us all an example of an honest and faithful relationship.’’

He added that the world is a better place “because Robert Irwin Sperber lived in it for 87 years.’’

Marvin Pave can be reached at marvin.pave@rcn.com.